Editor’s note: After noticing the huge number of posts and comments on Facebook that followed a book review in Morgenbladet newspaper in December by Espen Søbye, I asked Annemor Sundbø to explain the furor. A translation of the original review follows her overview.

DEN NORSKE STRIKKEKRIGEN – The Norwegian Knitting war

by Annemor Sundbø

Lately, Norwegian newspapers have been publishing long articles in defense of knitting, after a noted philosopher, author, biographer, and award-winning critic, Espen Søbye, reviewed a selection of the year’s knitting books that were in the holiday book section of Morgenbladet, a national newspaper. A debate on equality exploded. It was a controversial review that unleashed a spirited debate on women’s’ roles and women’s’ ideals. Was it a defeat for equality and the fight for women’s’ liberation? Or is the current popularity of knitting a purposeful renaissance of women’s’ traditional skills?

The collection of books that were chosen were richly illustrated books with many patterns. The reviewer felt they promoted an outdated feminine ideal and he wondered whether they actually encouraged women to be obedient and subservient to men. He emphasized that he was not attacking knitters, but he was attacking the books. He felt that the books idealized, and that the models were not representative of those the knitters knit for. The reviewer belittled knitters and they became, in a way, laughable.

But the reaction was strong because modern women don’t want their accomplishments and concerns to be regarded as something archaic, even if knitting has traditions tied to the home and housework. It can appear old-fashioned, laughable, and comic. Many family values are tied to that which is old-fashioned, while a career is something that is modern. Women’s hobbies, magazine-reading, and TV series, along with knitting, are often seen as domestic, and less important than men’s interests like wood-chopping, hunting, fishing, and beer-making, even if those are also nostalgic activities with roots in the old days.

Many newspaper pieces defend knitting as connected to women’s mental health, something that satire programs on TV try to exploit.

Gradually ”the Norwegian knitting war” took on enormous proportions; it was difficult to survey all the news coverage. Many of the pieces didn’t have much to do with the original topic. They merely defended knitting and its popularity. The critic, Espen Søbye, actually criticized the quality of a small selection of the year’s knitting books and gave his opinion on knitting as a phenomenon.

(Translated by Robbie LaFleur)

Between Knit and Purl

by Espen Søbye

Originally published as “Mellom rett og vrangt,” Morgenbladet, December 24, 2015

When looking at this year’s big sellers, knitting books, one can see a formidable battle over what kind of feminine ideal matters in today’s Norway.

How to explain the flood of knitting books? Many people buy these books because they like to knit. Is it necessary to make it more difficult than that? But why has the interest in knitting gained ground just now? To get to the bottom of this burning question, we confront nine of this year’s approximately 50 knitting books: four from Cappelen Damm, three from Gyldendal, one from Pax and one from J. M. Stenersen Company. In order to investigate them, it was necessary to put to use those parts of the consciousness that Freud felt that the super ego had forbidden. An investigation reveals that knitting books comprise a major component in a formidable battle over what kind of feminine ideal will matter in Norway as we approach the second decade of the 21st century.

Between family and weeklies. According to the bestseller list for nonfiction, the book published by the venerable J. M. Stenersen Company—now a subsidiary of Kagge—is the most-purchased, indeed, it is among autumn’s overall bestsellers. For many of us, it is entirely unfathomable that a book with a title that is painful merely to spell, Klompelompe, has been chosen by so many. Is this the nickname parents use for their beloved little ones nowadays?

Between family and weeklies. According to the bestseller list for nonfiction, the book published by the venerable J. M. Stenersen Company—now a subsidiary of Kagge—is the most-purchased, indeed, it is among autumn’s overall bestsellers. For many of us, it is entirely unfathomable that a book with a title that is painful merely to spell, Klompelompe, has been chosen by so many. Is this the nickname parents use for their beloved little ones nowadays?

All of the knitting books are written by and for women. Even so, it would be wrong to characterize them as part of a powerful political-feminist movement. Quite the opposite, these books pass on the very matters that are valued as traditionally feminine: the love of ornamental handwork, the desire to dress children well, the joy of homemaking—completely traditional values that we assumed were gone for good.

Maximalism is the style of choice in general in the forewords of these knitting books, and there is no lack of such big words as “spirit”, “love”, “harmony”, “nature.” Nearly every author emphasizes that knitting is a tradition, that they learned it from their mother or grandmother, and that it is a skill that is passed on in a family from one generation of women to the next. This is presented as something positive and desirable, and it gives knitting a value of its own—as a valuable and genuine activity.

Not one of the authors addresses the evident contradiction that these books contribute to and continue the idea that knitting belongs to women’s culture, but really doesn’t, or why would these books be necessary? How is it possible to sell tens of thousands of knitting books every year that tell the buyer that she should have learned the craft elsewhere?

A person asks whether illustrated weekly magazines—whose circulation numbers are in free fall—have been a more important mediator regarding knitting skills than idealized, trans generational women’s culture, and whether the knitting books are simply a continuation of weekly magazines with other resources.

Therapy in the web shop. A therapeutic argument recurs throughout these books: Through handwork, the knitter comes into contact with something natural and true. It is often emphasized what a lovely and relaxing break it is from being logged into the internet all the time. After having finished the sections that throw dirt on social media because it is improper to waste time on that sort of thing, the knitting book authors boast without restraint about their own Facebook pages, with their ten thousand members who share patterns and experiences. Most of the authors have web shops that sell various knitting-related products. Books are only one part of the whole business.

“We love good yarn and a good chat,” it says in the one translated book, Katherine Poulton’s Trendy strikk. 30 luer, skjerf og votter [Trendy Knitting : 30 Caps, Scarves, and Mittens. Original title: A Good Yarn]. Here lies a gentle and cautious, but nonetheless a clear, undertone of an alternative movement, and anti-commercialism: to buy a piece of clothing is alienating and impersonal. Of course, the book comes from the US, where new commercial successes are created just exactly like alternative movements. How critical of the system is it to buy yarn and patterns online instead of swinging by Hennes & Mauritz?

“We love good yarn and a good chat,” it says in the one translated book, Katherine Poulton’s Trendy strikk. 30 luer, skjerf og votter [Trendy Knitting : 30 Caps, Scarves, and Mittens. Original title: A Good Yarn]. Here lies a gentle and cautious, but nonetheless a clear, undertone of an alternative movement, and anti-commercialism: to buy a piece of clothing is alienating and impersonal. Of course, the book comes from the US, where new commercial successes are created just exactly like alternative movements. How critical of the system is it to buy yarn and patterns online instead of swinging by Hennes & Mauritz?

Coded language. The authors urge the reader to use her imagination. How odd. After all, how creative can it be to follow a detailed pattern? It undoubtedly requires precision and patience, but doesn’t this more closely resemble submission and obedience than independence? In this respect, the knitting books remind one of the coloring books for young adults that have become so popular. Is following a pattern a kind of intellectual bondage, or is it a coded message that shy Norwegian women send to the first man they meet that they could imagine themselves for a brief moment to be Anastasia Steele (the female protagonist in Fifty Shades of Grey)?

Knitting patterns are largely given as abbreviations, r standing for rett [knitted] and vr for vrang [purl], p for pinne [knitting needle], etc. The abbreviation “2i1” [2 in 1] ought to be a favorite with self-respecting quizmasters. To translate the abbreviation “3 r sm” feels like divulging the murderer’s name in a crime novel. Some things are, in spite of it all, most fun to find out for yourself.

Resistance against knitting. One of the books, Rett på tråden [Right on the Thread] differs from the others, not only with its slightly impudent title. In the introduction, sisters Birte and Margareth Sandvik quote the exchange of lines in A Doll’s House, where Torvald Helmer advises Mrs. Linde to set aside her knitting and take up embroidery instead, because knitting “can never be anything but ugly, “ “there’s something Chinese about it.”

Resistance against knitting. One of the books, Rett på tråden [Right on the Thread] differs from the others, not only with its slightly impudent title. In the introduction, sisters Birte and Margareth Sandvik quote the exchange of lines in A Doll’s House, where Torvald Helmer advises Mrs. Linde to set aside her knitting and take up embroidery instead, because knitting “can never be anything but ugly, “ “there’s something Chinese about it.”

Knitting has had several vocal opponents since Ibsen’s Torvald. In their book Crisis in the Population Question (1934), the married couple Alva and Gunnar Myrdal—both tone-setting Swedish social democrats, she winning the Nobel Peace Prize, he the Nobel prize for economics—were angered by the exaggerated petit bourgeois habits that had spread among the working class and minor civil servants. Family life in these classes was, according to the Myrdals, characterized by a fussy desire to entertain, an overly-ambitious interest in food and homemaking, with a penchant for public display. But it was, above all, women’s handwork that paid the price: “All this embroidery, this knitting, sewing, and lacemaking that has filled the walls and sofas, tables and shelves.”

Knitting became equated with a confined active mind and connected to married women’s having no right to work and the two-child family having become the norm.

Staying home with one or two children resulted in women’s having lots of free time—and presto, this is how Alva and Gunnar Myrdal explained the then-current knitting wave: Knitting and crochet were enterprise gone wrong. This energy should be used for something more practical for society and the individual.

At the end of the 20th and beginning of the 21st centuries, women are having even fewer children than did their grandmothers in the 1930s, and men’s and women’s lives have become almost exactly identical. The reduction in the number of childbirths is a major reason why the buxom female with broad hips and heaving breasts is no longer the ideal woman, instead the athletic, androgynous female body that exudes health and sex appeal is. The anorexic, boyish body has become the woman’s dream physiology, and she dresses accordingly.

Arne & Carlos. It is equally certain that, in the wake of the Christmas ornaments from Arne & Carlos, brand name for the Norwegian Arne Nerjordet and the Swede Carlos Zachrison, there has sprung up a female image that challenges the black-clad boy-women. Arne & Carlos have given women the courage to challenge unisex fashion and to feminize the classic knitted garments, socks, mittens, caps, pullovers, and cardigans that were so-called gender neutral. In Sidsel J. Høivik’s Vakker strikk [Beautiful Knitting], decorative, colorful, feminine, joyful, and affirming style has its renaissance. Here, feminine forms are in abundance, and the garments don’t hide them but, rather, emphasize them. Just imagine, cardigans with lace collars are launched here. Knitting books predict a reaction to and a break with the unwomanly woman’s image.

Arne & Carlos. It is equally certain that, in the wake of the Christmas ornaments from Arne & Carlos, brand name for the Norwegian Arne Nerjordet and the Swede Carlos Zachrison, there has sprung up a female image that challenges the black-clad boy-women. Arne & Carlos have given women the courage to challenge unisex fashion and to feminize the classic knitted garments, socks, mittens, caps, pullovers, and cardigans that were so-called gender neutral. In Sidsel J. Høivik’s Vakker strikk [Beautiful Knitting], decorative, colorful, feminine, joyful, and affirming style has its renaissance. Here, feminine forms are in abundance, and the garments don’t hide them but, rather, emphasize them. Just imagine, cardigans with lace collars are launched here. Knitting books predict a reaction to and a break with the unwomanly woman’s image.

The two competing feminine ideals—the androgynous and the buxom–are initiated by male designers, who do not have women as their primary, fascinating objects of desire. Arne & Carlos’s decorative, colorful, joyful and affirming style, where the wearers’ attributes can be both seen and exalted, and where there can be no doubt as to how they can be used, can be called Catholic. Here there is both sin and forgiveness. The image of woman, where the feminine is scraped away, is Protestant Pietistic, and it is this ideal that is challenged in these knitting books.

Dorthe’s revenge. The former glamor model, now TV hostess, Dorthe Skappel, doesn’t take part in the battle between the two feminine ideals. She leads another struggle. In Mer Skappelstrikk [More Skappel Knitting], she has—brave as she is—brought her knitting needles and yarn to Sweden, Alva and Gunnar’s homeland of anti-knitting. She spends every summer in a tent, she tells us, and offers herself to us, seasoning her book with photographs of the joys of camp life in the glorious landscape of Nord-Koster. Skappel is the vision in front of the tent, no longer clad in a bathing suit but in a wide, hand knit pullover, surrounded by knitting tools. Sunset over the bays of Hassle on one side, the pattern for a sweater dress with a split hem in the back on the other. A scene that invites us to sin in the summer sun, to saltwater swims and postcoital naps on the warm rocks inspired in Dorthe sweaters that resemble small tents.

Dorthe’s revenge. The former glamor model, now TV hostess, Dorthe Skappel, doesn’t take part in the battle between the two feminine ideals. She leads another struggle. In Mer Skappelstrikk [More Skappel Knitting], she has—brave as she is—brought her knitting needles and yarn to Sweden, Alva and Gunnar’s homeland of anti-knitting. She spends every summer in a tent, she tells us, and offers herself to us, seasoning her book with photographs of the joys of camp life in the glorious landscape of Nord-Koster. Skappel is the vision in front of the tent, no longer clad in a bathing suit but in a wide, hand knit pullover, surrounded by knitting tools. Sunset over the bays of Hassle on one side, the pattern for a sweater dress with a split hem in the back on the other. A scene that invites us to sin in the summer sun, to saltwater swims and postcoital naps on the warm rocks inspired in Dorthe sweaters that resemble small tents.

The person who finds Mer Skappelstrikk under the Christmas tree or who receives it directly from the man with the white beard can check to see for themselves whether or not Dorthe Skappel’s broad smile shines in triumph. The rest of us will have to rely on Morgonbladet’s reviews. She has every reason to smile. Her poses, sweaters, and socks demonstrate her transformation from Norway’s pinup number one to the country’s queen of knitting, none other than Madam “pins up”, as she is called in the Sandvik sisters’ Rett på tråden: She smiles indulgently at the Myrdals’ thesis, entices young women to dress in baggy sweaters—when she herself preferred tight-fitting swimsuits—all the while Norwegian kroner roll into her bank account for every stitch Norway’s women knit.

(Translated by Edi Thorstensson)

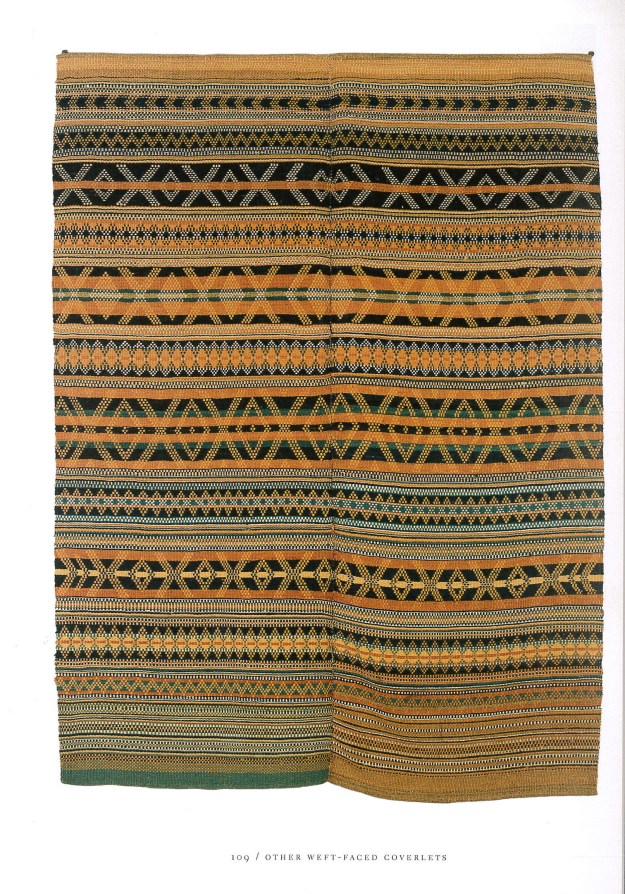

Weaving: Lila Nelson. One. Two. Three.

Weaving: Lila Nelson. One. Two. Three. At the time that American weavers were experimenting with danskbrogd, contemporary Norwegian weavers were inspired by the old coverlets, too. Betty Johanessen visited the museum in Kristiansand in the summer of 1997 and took this photo of three beautiful banded danskbrogd hangings. If anyone knows the weavers, let me know!

At the time that American weavers were experimenting with danskbrogd, contemporary Norwegian weavers were inspired by the old coverlets, too. Betty Johanessen visited the museum in Kristiansand in the summer of 1997 and took this photo of three beautiful banded danskbrogd hangings. If anyone knows the weavers, let me know!